Golden Years at Oxford

Jack Christian fondly narrates the early history of Materials Science at Oxford

THE DEPARTMENT OF MATERIALS at Oxford University recently celebrated 40 years of independent existence. The department was nucleated in 1917 when William Hume-Rothery, an army cadet at Woolwich, became infected with cebrospinal meningitis. He recovered from this serious illness but was left totally deaf and with a very poor sense of balance and his promising military career was obviously ended. Whereas the army lost a future general, Oxford ultimately gained a Department of Materials.

Hume-Rothery

The youthful Hume-Rothery read chemistry at Oxford with distinction despite his disability and then worked for his PhD at the Royal School of Mines in London. Upon his return to Oxford with a newly found enthusiasm for work on alloys, he was given a little bench space in the Dyson-Perrins laboratory and was later accommodated in the old chemistry department which was eventually called the Inorganic Chemistry Department (ICL). In cramped accommodation, he began the long series of investigations into alloy equilibria and the inspired hypotheses which led to the famous Hume-Rothery Rules. For many years, his workplace in the DP laboratory was marked by a circular depression in the floor boards illustrating the reaction between molten copper and wood.

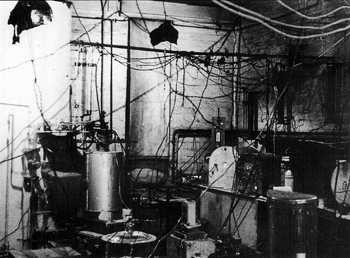

By 1945, HR had graduated to two and a half rooms. HR sat at a desk in one of these (a separate office was an unheard of luxury) and wrote his books, occasionally emerging to help the research along by volunteering to measure up an x-ray film. The second room contained a special vibration-free potentiometer bench, innumerable furnaces for heat treatment, a travelling microscope for measuring x-ray films and in one corner, shielded by a sheet of lead mounted on a table, the Metropolitan Vickers x-ray unit, fig 1.

HR was on some important government committees, including the Interservices Metallurgical Research Council, and it became one of my jobs to accompany him to meetings, write down what was being said and catch the chairman's eye when he wanted to speak. It was stimulating to a young man to be privy to many secrets and to see how some famous scientists conducted themselves but the job was not without its hazards. Several times, the time lag between someone's remark and HR's grasp of it would result in my 'shooting him up' too late when the chairman had already passed on to the next item; some chairmen were relaxed about this and others were not! But the worst difficulties came from HR's habit of issuing instructions in what he thought was a quiet whisper but which carried clearly around the room. 'Do not bother writing this down, this man always talks rubbish.' During the time I was a research student, HR was publishing what later became one of his most popular books Electrons, atoms, metals and alloys as a series of articles in a magazine called Metal Industry. The articles took the form of a platonic dialogue between an older metallurgist and a younger scientist and were broadly about the electron theory of metals. As research students, we were given the task of reading the proofs which arrived regularly at two week intervals, and we had sometimes had to delicately indicate that HR's attempts to reproduce current slang were not quite up to date.

Laboratory

One of the two rooms occupied by Hume-Rothery in the old chemistry department in the early days of metallurgical research at Oxford (ca 1950)

The idea of a separate department at Oxford arose gradually. I was appointed departmental demonstrator in 1951 and initially began lectures on metallurgical topics to chemists who were able to register for metallography as a supplementary subject in the Final Honour School. The then Pressed Steel Company at Oxford sponsored research fellowships at the university, one of which I held, and they established a readership in Metallurgy named after their managing director George Kelly, and in 1954 HR became the first George Kelly Reader. I was appointed lecturer in metallurgy in 1955 and John Martin came from Cambridge to be our second lecturer in 1957. Angus Hellawell, having just taken his PhD also joined us as graduate assistant to HR.

During the 1950s, governmental pressure for increased provision in engineering, combined with a belief in the university that the Oxford Engineering Department was too small, led to the establishment of an advisory committee with members drawn from Cambridge (which had a large and successful engineering school), government research, industry and the university. The committee recommended doubling the size of the department and trebling the floor area. Opposition to the expansion came from Lord Cherwell who thought engineering was best left to colleges of technology, the Vice Chancellor and Professor Sir Cyril Hinshelwood who ruled over both the physical chemistry and the inorganic chemistry laboratories.

Whether this antipathy towards engineering carried over to metallurgy I do not know, but the atmosphere changed markedly when 'Sir Francis Simon became head of the Clarendon and CM

Bowra became Vice Chancellor. Simon was very interested in developing metallurgical studies, but the real surprise was Bowra. To our astonishment, this high priest of classical culture proved to be very sympathetic to our cause and together with the registrar, Sir Douglas Veale, he gave us much help and encouragement. Simon's idea was to set up a research institute on the lines of the Laboratory for the Study of Metals in Chicago, which had impressed him. An industrial appeal committee was organized under the chairmanship of Major Pam of the Pressed Steel Company, and was run largely by GL Bailey of the British Non Ferrous Research Association and CJ Smithells of British Aluminium Ltd. The appeal was not a success and only raised about £40,000; Bailey and Smithells attributed this to the emphasis on research and stated that what British industry would like was a teaching department. So the emphasis was shifted to include much more teaching and an honour school was devised with a degree course initially based on the chemistry course with Metallurgy replacing organic chemistry and the fourth year being spent on a metallurgical project. When this proposal came to the Board of the Faculty of Physical Sciences, it insisted that a degree in scientific metallurgy should contain 'no more technology than is involved in the degree courses of chemistry or physics' and it stated that 'the man who has studied pure science at a university can take up technology on entering industry much more easily than one who has studied technology can later take up the pure science which maybe required for his work'.

Money for a new building was obtained from a new UGC technology initiative. The building was twice scaled down in size at the planning stage and was eventually built for £100,000 plus fees, and after spending two spartan years in a very old laboratory we moved in there in 1959. In the meantime, moves had been made to secure a chair for HR, a prime activist being Dr HM Finniston (Monty) head of the Metallurgy Division at AERE Harwell. We had, of course, very good contacts at Harwell, especially via the Oxford Metallurgical Society which was recognised as a local section of The Institute of Metals and which had been founded jointly by our department and the Metallurgy Division at AERE. Through an intermediary, Monty interested Sir Isaac Wolfson in the project and this eventually led to the Wolfson chair of Metallurgy which HR held until his retirement in 1966. The chair was subsequently held by Sir Peter Hirsch from 1966-1992 and the present professor is David Pettifor.

From the beginning, the research effort at the department grew strongly and with visitors and research fellowships it was soon firmly established as a leading centre for basic research on materials. Whereas the research prospered, undergraduates were hard to find and it was a long slow haul up to our present numbers. Nevertheless when HR retired in 1966, he must have felt satisfaction in knowing that not only had he created a major research department, hut he had also made an important contribution to the teaching of metallurgy in Britain. Sadly, HR lived for only two years after his retirement.

I have tried to give a picture of the Hume-Rothery years of metallurgy at Oxford, a subject which was already turning into the broader field of materials at the time of his retirement. The subsequent rapid expansion of the department belongs to the Hirsch years and is an equally fascinating story, but one which will be fresh in many memories

Professor JW Christian FRS, Department of Materials, University of Oxford

Reprinted from Materials World, Volume 5, Number 4.